Tenses

Past, Present, Future

A helpful trick to remember the tense prefixes is by using the common girls name "Natalie". Except in our case, its "na-ta-li".

| Tense |

Verb Prefix |

| Present |

na |

| Future |

ta |

| Past |

li |

Here is an example of the conjugations of "-lala" the verb for "sleep". The pronoun prefix is in blue. The tense prefix is in red.

| Pronoun |

Past |

Present |

Future |

| mimi |

nililala |

ninalala |

nitalala |

| wewe |

ulilala |

unalala |

utalala |

| yeye |

alilala |

analala |

atalala |

| sisi |

tulilala |

tunalala |

tutalala |

| ninyi |

mlilala |

mnalala |

mtalala |

| wao |

walilala |

wanalala |

watalala |

Note: You may see verbs shown in two flavours. The infinite form, starting with the prefix "ku". For example, "kulala" means "to sleep".

You may also see verbs in their root form, which uses a hyphen "-" instead of "ku" to denote that you will use prefixes where the dash is.

For example, "-lala" mentioned above means "sleep" when paired with appropriate prefixes.

Advanced Tenses

"-me" Tense

The first advanced tense we will cover is the "-me" tense. This is often referred to as the "Present Perfect" tense. Something we don't exactly have in English.

*NOTE: This is always used with the positive verbs. The opposite/negation of this, is the -ja tense found below.

Translations of "-me" verbs will vary based on the verb definition. However, we can group "-me" verbs into two categories:

- Passive Verbs:

With positive-passive verbs, this is similar to saying "is currently in the state of". What I mean by this, is best explained with example. Take the verb -potea" (to be lost).

If you wish to say "he is lost", you will use amepotea.

This is similar to saying "he is currently in the state of being lost at this moment." Compare this with the following conjugations:

| Tense |

Swahili |

English |

| Present |

anapotea |

He is becoming lost. |

| Past |

alipotea |

He got lost. |

| Future |

atapotea |

He will get lost. |

| Present Perfect |

amepotea |

He is lost. |

*NOTE: The opposite of this (for negative verbs --> i.e. "He is NOT lost") is the -ja tense found below!

- Active verbs:

When pared with an active verb, it is similar to the Past Perfect in English. (a.k.a. "He ran" vs. "He has run". The "have + run" form is the Past Perfect. This can also be formed using "-me" verbs.

For example, take the verb "-soma" (to study). Here are the following conjugations:

| Tense |

Swahili |

English |

| Present |

ninasoma |

I am studying. |

| Past |

nilisoma |

I studied. |

| Future |

nitasoma |

I will study. |

| Past Perfect |

nimesoma |

I have studied. |

*NOTE: The opposite of this (for negative verbs --> i.e. "He has NOT studied") is the -ja tense found below!

"-ja" Tense

The "-ja" tense is basically the opposite of the "-me" tense from above. It is colloquially referred to as the "not yet" tense.

You use this tense to say that some event has not yet taken place, or some action is not done yet.

*NOTE: this tense is ALWAYS used with the negative. For positive versions of these, see the -me tense above.

*NOTE2: The word "bado" (yet, still) is often used in conjunction with this tense.

For example, we will use the verb "-fika" (to arrive):

| Pronoun |

Swahili |

English |

| mimi |

sijafika |

I have not arrived (yet). |

| wewe |

hujafika |

You have not arrived (yet). |

| yeye |

hajafika |

He has not arrived (yet). |

| sisi |

hatujafika |

We have not arrived (yet). |

| ninyi |

hamjafika |

You all have not arrived (yet). |

| wao |

hawajafika |

They have not arrived (yet). |

*NOTE: For single syllable words (kuja, kula, etc) they generally DROP the "ku" (unlike other language constructs, which usually keep the "ku"):

| Swahili |

English |

| sijala |

I have not eaten. |

"-mesha" Tense

The "-mesha" tense is very similar to the -me tense above. (Technically, it is an extension of the -me tense. See below the example for a grammatic explanation).

The main difference is, this tense specifies something that "has already" happened. It is easiest explained with an example:

| Tense |

Kiswahili |

English |

| present |

Ninaenda |

I am going |

| -me |

Nimeenda |

I am gone. |

| -mesha |

Nimeshaenda |

I have already gone. |

This form is actually a contraction. (Such as "do" + "not" == "don't").

It combines: "-me" + "kwisha" to get mesha

*NOTE: "-kwisha" means "to finish". Therefore the above example translates directly to something like "He has finished going" implying he already finished doing the act of going.

Numbers

Numbers: 0-10

The basic numbers 0-10 are pretty simple:

| Number |

Kiswahili |

| 0 |

sifuri |

| 1 |

moja* |

| 2 |

mbili* |

| 3 |

tatu |

| 4 |

nne |

| 5 |

tano |

| 6 |

sita |

| 7 |

saba |

| 8 |

nane |

| 9 |

tisa |

| 10 |

kumi |

*Note: Cardinal numbers "one" and "two" are equivalent to "moja" and "mbili". However, when using ordinal numbers (first, second, third... etc), "first" and "second" correspond to "kwanza" and "pili". All other numbers are the same for both cardinal and ordinal numbers.

Numbers: Teens (11-19)

For numbers 11 to 19, you use the form

. This is pretty logical since it basically says "ten and one", or "eleven" in English.

| Number |

Kiswahili |

| 11 |

kumi na moja |

| 12 |

kumi na mbili |

| 13 |

kumi na tatu |

| 14 |

kumi na nne |

| 15 |

kumi na tano |

| 16 |

kumi na sita |

| 17 |

kumi na saba |

| 18 |

kumi na nane |

| 19 |

kumi na tisa |

Numbers: Tens (20, 30, etc)

For the tens column (20, 30, 40, ... 90) things get REALLY weird. Some of these have roots from the basic 1-9 numbers, but a handful are borrowed from Arabic so all bets are off. Just memorize these. Sorry. However I do my best to use blue to show any roots that stem form the earlier numbers.

Note: You just use "na" to join on more numbers ("thousands" na "hundrends" na "tens" na "ones"). For example, twenty-one (21) is written as "twenty and one" or

| Number |

Kiswahili |

| 20 |

ishirini |

| 30 |

thelathini |

| 40 |

arobaini |

| 50 |

hamsini |

| 60 |

sitini |

| 70 |

sabini |

| 80 |

themanini |

| 90 |

tisini |

Numbers: Hundreds

The hundreds column (100, 200, 300 ... 900) follow a nice trend. They use the word "mia" or "hundred". So "mia moja" is equivalent to "one hundred".

| Number |

Kiswahili |

| 100 |

mia moja |

| 200 |

mia mbili |

| 300 |

mia tatu |

| 400 |

mia nne |

| 500 |

mia tano |

| 600 |

mia sita |

| 700 |

mia saba |

| 800 |

mia nane |

| 900 |

mia tisa |

Numbers: Thousands

The thousands column (1000, 2000, 3000, ... 9000) behave very similar to the hundreds, except they use the word "elfu" or "thousand". So "elfu moja" translates to "one thousand".

| Number |

Kiswahili |

| 1000 |

elfu moja |

| 2000 |

elfu mbili |

| 3000 |

elfu tatu |

| 4000 |

elfu nne |

| 5000 |

elfu tano |

| 6000 |

elfu sita |

| 7000 |

elfu saba |

| 8000 |

elfu nane |

| 9000 |

elfu tisa |

Numbers: Ridiculously Large

The pattern for forming large numbers in Swahili is mostly the same, even into the super large numbers. They also use similar large numbers as in English: milioni == million, bilioni == billion, etc.

| Number |

Kiswahili |

English |

| 10,000 |

elfu kumi |

ten thousand |

| 20,000 |

elfu ishirini |

twenty thousand |

| 30,000 |

elfu thelathini |

thirty thousand |

| 100,000 |

elfu mia moja |

one hundred thousand |

| 200,000 |

elfu mia mbili |

two hundred thousand |

| 300,000 |

elfu mia tatu |

three hundred thousand |

| 1,000,000 |

milioni moja |

one million |

| 2,000,000 |

milioni mbili |

two million |

| 3,000,000 |

milioni tatu |

three million |

| 10,000,000 |

milioni kumi |

ten million |

| 20,000,000 |

milioni ishirini |

twenty million |

| 30,000,000 |

milioni thelathini |

thirty million |

| 100,000,000 |

milioni mia moja |

one hundred million |

| 1,000,000,000 |

bilioni moja |

one billion |

| 1,000,000,000,000 |

trilioni moja |

one trillion |

| 1,000,000,000,000,000 |

kwadrilioni moja |

one quadrillion |

Telling Time

The first thing to know, is that Swahili days center around 7 AM and 7 PM instead of midnight and noon (12's) in USA times.

We will start off with a trick to telling time based on a clock. If you have a clock using standard American timetelling hands, you can determine the Kiswahili time by adding or subtracting 6 hours. (This can be visualized by looking at the the exact opposite number of the hour hand. Aka, half a circle.)

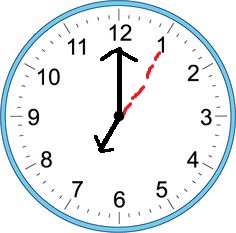

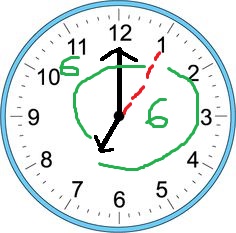

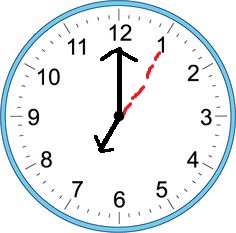

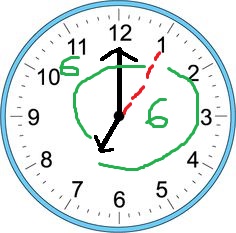

Example (7 o'clock in USA -> 1 o'clock in Kiswahili):

Notice that 6 hours in either direction make the semi-circle that relate the times:

*NOTE: According to the book, some people in Swahili speaking countries actually use their watches like this. They tune it to "American-style" time and just read the opposite hour as seen in the pictures above.

Now for some Kiswahili. Two useful keywords/phrases to know are saa ("hour" in English) and saa ngapi? ("what time is it?").

The follow chart shows how you distinguish 7 AM from 7 PM. In Kiswahili you use asubuhi to mean morning, or jioni/usiku to mean evening or night respectively.

| Time |

Kiswahili |

English Translation |

| 7 AM |

saa moja asubuhi |

first hour in the morning |

| 7 PM |

saa moja jioni/usiku |

first hour of the evening/night |

So in order to tell time, you can simply change the number to offset from 7 AM/PM. Here are some examples:

| Time |

Kiswahili |

| 10:00 AM |

saa nne asubuhi |

| 12:00 PM (noon) |

saa sita asubuhi |

| 5:00 PM |

saa kumi na moja asubuhi |

| 8:00 PM |

saa mbili jioni/usiku |

| 11:00 PM |

saa tano jioni/usiku |

| 12:00 AM (midnight) |

saa sita jioni/usiku |

Now to get a bit more interesting. Here is how you can say 15, 30, or 45 minutes on the hour.

For 15 or 30 minutes, you use na to add robo (quarter) or nusu (half).

For 45 minutes, you use subtraction. You say something along the lines of "15 minutes before ..." So you use kasarobo (minus a quarter) with the next hour. For instance, 3:45 would be "15 minutes before 4".

Here are some examples:

| Time |

Kiswahili |

| 5:15 AM |

saa kumi na moja na robo usiku |

| 2:30 PM |

saa nane na nusu asubuhi |

| 8:45 PM |

saa tatu kasarobo jioni |

To get a bit more specific, you use the words dakika (minutes) along with na (add) and kasa (less [subtract]).

Here are some examples:

| Time |

Kiswahili |

| 7:55 PM |

saa mbili kasa dakika tano usiku |

| 9:02 AM |

saa tatu na dakika mbili asubuhi |

The best way to learn this is to do a TON of practice. Truth be told, I quadruple checked myself on most of these and still may have made a mistake. Don't forget to use the sidebar to email me with any errors so that I can correct them! :D

Object Prefixes

When taking a direct/indirect object in Kiswahili, they add another prefix after the tense prefix.

Some examples of this would be "reading TO someone", or "cooking FOR someone". You can technically use this form on any verb, but it doesn't always make sense. You usually cannot "sleep FOR someone" for example It just doesn't make much sense.

*NOTE: If you wanted to do an action to yourself, such as "cook FOR yourself", then use the Reflexive.

If you recall from earlier lessons, we usually form verbs like so:

Pronoun Prefix + Tense Prefix + Verb Root

We will form the new verbs like so:

Pronoun Prefix + Tense Prefix + Object Prefix + Modified Verb

Before some explanation and examples, we will provide you with some charts:

The first chart shows the new prefix. Half of them are the same as the pronoun prefix, the other half are different. I denote the different ones using red.

| Pronoun |

Pronoun Prefix |

Object Prefix |

| mimi |

ni |

ni |

| wewe |

u |

ku |

| yeye |

a |

m |

| sisi |

tu |

tu |

| ninyi |

m |

wa |

| wao |

wa |

wa |

This next chart will make more sense with some examples, but when using this form you have two different types of ending changes for your verbs.

The first is -ia and the other is -ea. To determine which to use, check the word for the main vowel that you pronounce (usually this is the first).

For example, take "-soma" and "-pika", the main vowels in each are: "-soma" and "-pika".

You use the chart below to determine which ending to use based on the root vowel:

| Root Verb Vowel |

Ending |

| i, a, u |

-ia |

| e, o |

-ea |

Following this chart, "-soma" becomes "-somea" and "-pika" becomes "-pikia". To use these in some sentences:

| English |

Kiswahili |

| I cook for you. |

Mimi ninakupikia. |

| I read to you (pl.). |

Mimi niliwasomea. |

| They will cook fish for me. |

Wao watanipikia samaki. |

| He reads to us. |

Yeye anatusomea sisi. |

*NOTE: In the fourth sentence, the "sisi" is optional. The tu identifies that the action is being done "to us", but we can add "sisi" for clarity as necessary.

There is one more thing to note: when forming this new verb form, if the verb would end in a vowel you add an L before the ending from the chart above. This helps with pronunciation.

For instance, take the verb "-nunua". Following the rules from above, "-nunua" would become "-nunuia". Pronouncing this is a little odd with the triple vowel, so we add an L to make it simpler to say: "-nunulia".

Passive Voice

Much like in English, Kiswahili also has passive voice. Passive Voice is described as a sentence in which the object is the subject. (Yeah, confusing right?) Well, not really. With an example, it becomes much more clear:

Take the following example:

The child cooks pizza.

As you can see, the subject is the "child". The verb is the action of "cooking". And the object is the "pizza" (the thing being cooked).

Another way you could say this would be by reversing the subject/object and using introducing the verb "to be":

The pizza is cooked by the child.

Now, as you can clearly see, the subject is the pizza and the object is the child. This is called the Passive Voice. The child is still technically doing the "cooking", except now the thing being cooked (pizza) is the subject of the sentence.

Finally time for some Kiswahili. They use it very similarly to English, however instead of adding "to be" as seen in the examplse above, Kiswahili adds a suffix to the verb.

The passive voice is formed by adding the one of the following suffixes to your verb: -wa, -liwa, and lewa. This vary based on the root vowel of the verb.

*NOTE: The patterns for the suffixes are similar to the Object Prefixes. For convience I'll map them out here:

1. If the root-verb ends in a consonant:

| Consonant |

Ending |

| Any Consonant Ending |

-wa |

2. If the root-verb ends in a vowel, analyze the ROOT vowel:

| Root Verb Vowel |

Ending |

| i, a, u |

-liwa |

| e, o |

-lewa |

Lastly, for the good stuff. Here is an active/passive example in Kiswahili using the same sentence as the English ones above:

| Active/Passive |

Kiswahili |

English |

| Active |

Mtoto anapika piza. |

The child cooks pizza. |

| Passive |

Piza anapikwa na mtoto. |

The pizza is cooked by the child. |

Noun Classes

Noun classes are probably one of the hardest parts of learning a bantu language (which Kiswahili is). The good thing is, you have probably been doing this (to some degree) already!

To start out, I will provide you with a scary chart that has everything you need to know about the basics of noun classes (Note: We will focus on classes 1-10 since they are used most commonly):

| Class |

Noun |

Adj. |

Prefix |

Negation |

-a (of) |

Poss. |

| 1 |

mtu |

mzuri |

a-/yu-* |

ha-/hayu-* |

wa |

wangu |

| 2 |

watu |

wazuri |

wa- |

hawa- |

wa |

wangu |

| 3 |

mti |

mzuri |

u- |

hau- |

wa |

wangu |

| 4 |

miti |

mizuri |

i- |

hai- |

ya |

yangu |

| 5 |

*Ø-jina |

*Ø-zuri |

li- |

hali- |

la |

langu |

| 6 |

majina |

mazuri |

ya- |

haya- |

ya |

yangu |

| 7 |

kitu |

kizuri |

ki- |

haki- |

cha |

changu |

| 8 |

vitu |

vizuri |

vi- |

havi- |

vya |

vyangu |

| 9 |

**ndizi |

nzuri |

i- |

hai- |

ya |

yangu |

| 10 |

**ndizi |

nzuri |

zi- |

hazi- |

za |

zangu |

| 11 |

ulimi |

mzuri |

u- |

hau- |

wa |

wangu |

| 14 |

uhuru |

mzuri |

u- |

hau- |

wa |

wangu |

| 15 |

kutaka |

kuzuri |

ku- |

haku- |

kwa |

kwangu |

| 16 |

mezani |

pazuri |

pa- |

hapa- |

pa |

pangu |

| 17 |

mezani |

kuzuri |

ku- |

haku- |

kwa |

kwangu |

| 18 |

mezani |

mzuri |

m(u)- |

ham(u)- |

mwa |

mwangu |

Now that we got the scary part out of the way, let us start breaking down the columns to make sense of this mystery. Keep in mind, eventually you will need to more-or-less memorize this whole table. Luckily most of them follow a pattern and you will pick up a lot of the most common noun classes through repetition during your studies.

Which nouns go to which class?

I will start by breaking down what each column means, with examples and explaination. Take the first two noun classes (1 and 2). We will start with the Noun column:

| Class |

Noun |

Adj. |

Prefix |

Negation |

-a (of) |

Poss. |

| 1 |

mtu |

mzuri |

a-/yu-* |

ha-/hayu-* |

wa |

wangu |

| 2 |

watu |

wazuri |

wa- |

hawa- |

wa |

wangu |

The Noun column is simply an example of the type of nouns that fall into these categories. For the first 10 noun classes, the classes are grouped in pairs: 1 & 2, 3 & 4, 5 & 6, 7 & 8, 9 & 10; where the first class is for singular words, and the second class is for the plural.

In this example, the word used was "mtu" meaning "person", with the plural "watu" meaning "people".

It should be noted that I color coated the prefix that changes between the singular and plurals in red with the root of the word in blue. This is because the noun classes are most easily recognized by their prefixes (especially the plural form prefix!) For example:

- Class 1 & 2 = m-/wa-

- Class 3 & 4 = m-/mi-

- Class 5 & 6 = *Ø-/ma-

- Class 7 & 8 = ki-/vi-

- Class 9 & 10 = **n-/n-

As you can see, by following the patterns in the prefixes of nouns (specifically the prefix of the plural), you can identify which class you should be using.

*NOTE: For Class 5, we use the symbol "Ø". This symbol is used because Class 5 nouns may take different prefixes(or possible none at all). This is another reason why you should classify these nouns by their plural prefix of ma.

**Note: Class 9 & 10 nouns are the same for the singular and plural. For instance, in English we can have one "sheep" or many "sheep". There is no plural such as "sheeps". These noun classes behave the same way. The example used above is "ndizi" meaning one or more "banana(s)".

Adjective Prefixes

Now that we know how to identify which class we put nouns into, we can begin using the other columns in the chart. Up next we have Adjectives. In Kiswahili, nearly all adjectives take a prefix and occur AFTER the noun of which they modify. The chart uses the example of "-zuri" being the root word meaning "good; great; beautiful":

| Class |

Noun |

Adj. |

Prefix |

Negation |

-a (of) |

Poss. |

| 1 |

mtu |

mzuri |

a-/yu-* |

ha-/hayu-* |

wa |

wangu |

| 2 |

watu |

wazuri |

wa- |

hawa- |

wa |

wangu |

Unfortuntely, this part requires some memorization. For each noun class, there is a different prefix that is used for adjectives describing a noun within that class. Luckily, for the first 10 noun classes, the prefix of the noun is also the prefix for adjectives. (This is purely by coincidence, but its helpful for remembering).

For example, to say "the good people", we look up the word "people" and find "watu". Since the prefix is wa-, we know it is in Class 2. Then we look up the adjective for "good" and find -zuri. Lastly, we remember (or consult the lovely chart) to find the prefix for Class 2 adjectives is coincidentally also "wa-". Now we put it all together: watu wazuri.

*NOTE: A very important exception to this rule applies here for all animate nouns (nouns that describe living things -- such as humans, animals, etc). All animate things (even when they are in a different class), use the m- or wa- adjective prefixes from Class 1 or 2 respectively. This is just something you need to know. Here is a common example:

Rafiki (the word for "friend(s)") is a word in Class 9 & 10 (the singular and plural are the same). Normally, Class 9 & 10 would use n- for both singular and plural, but since friends are living people, they use m- and wa-. So if you have a "good friend", you would have: Rafiki mzuri.

Verb/Subject Prefixes

This next part should look very, very similar to you, because it is what we have been doing to conjugate verbs for Pronouns. Basically whenever you use a noun as a subject, instead of using "ni", "u", "a", etc. we will use the prefix from the chart. This can be applied to verb conjugations, Object Prefixes, Places, etc.

| Class |

Noun |

Adj. |

Prefix |

Negation |

-a (of) |

Poss. |

| 1 |

mtu |

mzuri |

a-/yu-* |

ha-/hayu-* |

wa |

wangu |

| 2 |

watu |

wazuri |

wa- |

hawa- |

wa |

wangu |

The easiest way to see this is to compare Class 1 nouns with yeye. Since yeye is the third-person pronoun, it can be used to replace most of the nouns from Class 1 because it contains people words.

If you look in the chart, you will notice that Class 1 and yeye take the same prefix: a- (or yu- for Places).

This can be very easily explained with an example. For instance, if you said: "he sings", you know "he" is "yeye" and "sing" is "-imba", so you form the sentence: Yeye anaimba.

Now imagine that you want to say "the child sings". You know the word for "sing" ("-imba"). You know the word for "child" ("mtoto"). But now what? Well, similarly to adjectives, you determine mtoto is Class 1 because it is the singular of mtoto/watoto which matches the first pair of classes: m/wa. Then you look into the table and see Class 1 uses the prefix a-. This produces the sentence: Mtoto anaimba.

You can apply this same process for any noun. Just determine what class it is from, and use the prefix in the table for the appropriate class instead of the a- in this example.

*NOTE: There is one, very important exception to this rule for all animate nouns (nouns that describe living things -- such as humans, animals, etc). All animate things (even when they are in a different class), use the a- or wa- prefixes from Class 1 or 2 respectively. This is just something you need to know. Here is a common example:

Rafiki (the word for "friend(s)") is a word in Class 9 & 10 (the singular and plural are the same). Normally, Class 9 & 10 would use i- and zi-, but since friends are living people, they use a- and wa-. So if your "friend sings", you would have: Rafiki anaimba.

Negation Verb/Subject Prefixes

These function basically the same was as Negation, and follow the same pattern mentioned above (in terms of how you find which prefix to use). So I am just gonna give you an example:

| Class |

Noun |

Adj. |

Prefix |

Negation |

-a (of) |

Poss. |

| 1 |

mtu |

mzuri |

a-/yu-* |

ha-/hayu-* |

wa |

wangu |

| 2 |

watu |

wazuri |

wa- |

hawa- |

wa |

wangu |

Imagine that you now want to say "the child does not sing". You know the word for "sing" ("-imba"). You know the word for "child" ("mtoto"). But now what? Well, similarly to adjectives, you determine mtoto is Class 1 because it is the singular of mtoto/watoto which matches the first pair of classes: m/wa. Then you look into the table and see Class 1 uses the negation prefix ha-. This produces the sentence: Mtoto haimbi.

*NOTE: The same, very important exception to this rule applies here too, for all animate nouns (nouns that describe living things -- such as humans, animals, etc). All animate things (even when they are in a different class), use the ha- or hawa- negation prefixes from Class 1 or 2 respectively. This is just something you need to know. Here is a common example:

Rafiki (the word for "friend(s)") is a word in Class 9 & 10 (the singular and plural are the same). Normally, Class 9 & 10 would use hai- and hazi-, but since friends are living people, they use ha- and hawa-. So if your "friend does not sings", you would have: Rafiki haimbi.

Of

This may seem kind of silly to an English speaker, but the word "of" changes based on the noun it follows. The root for "of" is technically -a, so you will notice the prefixes will more-or-less match the prefixes we used for adjectives. But they are NOT always the same, so it is best to just learn these seperately (most of them are 2 or 3 letter words anyhow).

As always, I will present you with an example that should be pretty self-explainitory:

| Class |

Noun |

Adj. |

Prefix |

Negation |

-a (of) |

Poss. |

| 1 |

mtu |

mzuri |

a-/yu-* |

ha-/hayu-* |

wa |

wangu |

| 2 |

watu |

wazuri |

wa- |

hawa- |

wa |

wangu |

Let's say you want to write the sentence "the child of Bob". We know "child" is "mtoto". Well, similarly to above, you determine mtoto is Class 1 because it is the singular of mtoto/watoto which matches the first pair of classes: m/wa. Then you look into the table and find the appropriate word for "of" being wa. Then you put it all together to get: mtoto wa Bob.

*NOTE: A very important exception to this rule applies here too, for all animate nouns (nouns that describe living things -- such as humans, animals, etc). All animate things (even when they are in a different class), use the wa version for "of" from Class 1 or 2. This is just something you need to know. Here is a common example:

Rafiki (the word for "friend(s)") is a word in Class 9 & 10 (the singular and plural are the same). Normally, Class 9 & 10 would use ya or za respectively, but since friends are living people, they use wa. So if there is a "friend of Bob", you would have: Rafiki wa Bob.

Possessives

If you aren't familiar with the root words for possessives, review them here: Possessives. Possessives for noun classes work the same way, except they will use the prefixes from the table. (Note: These ones ARE the same as the "of" words. Maybe that will make it easier to remember. Or else just learn them seperately).

Once again, I will leave you with a simple example that should be self-explainitory:

| Class |

Noun |

Adj. |

Prefix |

Negation |

-a (of) |

Poss. |

| 1 |

mtu |

mzuri |

a-/yu-* |

ha-/hayu-* |

wa |

wangu |

| 2 |

watu |

wazuri |

wa- |

hawa- |

wa |

wangu |

Let's say you want to write the sentence "my child". We know "my" is translated to the base word of "-angu". We know "child" is "mtoto". Well, similarly to above, you determine mtoto is Class 1 because it is the singular of mtoto/watoto which matches the first pair of classes: m/wa. Then you look into the table and find the appropriate possessive prefix w-. Then you put it all together to get: mtoto wangu.

*NOTE: The most complicated (but similar to exceptions above) applies here for SOME animate nouns (nouns that describe living things -- such as humans, animals, etc). Animate nouns that are NOT in Class 9 & 10, use the w- possessive prefixes from Class 1 or 2 respectively. REMEMBER: This does NOT apply to Class 9 & 10. This is just something you need to know. Here is an example to distingush:

| Class |

Noun |

English |

Example |

| 9 |

Rafiki (sg.) |

My friend |

Rafiki yangu |

| 10 (or 6) |

Rafiki (pl.) |

My friends |

Rafiki zangu |

| 7 |

kiongozi |

My leader |

Kiongozi wangu |

| 8 |

viongozi |

My leaders |

Viongozi wangu |

Places

To talk about location, you will use three types of words. Their roots are "-po", "-ko", and "-mo".

We will start with their usages/meaning:

| Kiswahili |

Meaning/Usage |

| -po |

Specific location ("is right here") |

| -ko |

General location ("is at/is on") |

| -mo |

Internal location ("is inside of") |

The format for these are:

pronoun prefix + -po/-ko/-mo

Here are some examples in present tense:

| Pronoun |

-po/-ko/-mo |

Present (+) |

Negation (-) |

| mimi |

-po |

nipo |

sipo |

| wewe |

-ko |

uko |

huko |

| yeye* |

-mo |

yumo* |

hayumo* |

| sisi |

-po |

tupo |

hatupo |

| ninyi |

-ko |

mko |

hamko |

| wao |

-mo |

wamo |

hawamo |

*NOTE: In the third-person singular (i.e. "yeye" case), the prefix changes from "a" to "yu" ("ha" to "hayu") for locations

For the past tense, you use the past tense of kuwa merged with -po/-ko/-mo as a single word:

| Pronoun |

-po/-ko/-mo |

Past (+) |

Negation (-) |

| mimi |

-po |

nilikuwa(po) |

sikuwa(po) |

| wewe |

-ko |

ulikuwa(ko) |

hukuwa(ko) |

| yeye |

-mo |

alikuwa(mo) |

hakuwa(mo) |

| sisi |

-po |

tulikuwa(po) |

hatukuwa(po) |

| ninyi |

-ko |

mlikuwa(ko) |

hamkuwa(ko) |

| wao |

-mo |

walikuwa(mo) |

hawakuwa(mo) |

Here is the future tense. It is formed similarly to the past tense:

| Pronoun |

-po/-ko/-mo |

Future (+) |

Negation (-) |

| mimi |

-po |

nitakuwa(po) |

sitakuwa(po) |

| wewe |

-ko |

utakuwa(ko) |

hutakuwa(ko) |

| yeye |

-mo |

atakuwa(mo) |

hatakuwa(mo) |

| sisi |

-po |

tutakuwa(po) |

hatutakuwa(po) |

| ninyi |

-ko |

mtakuwa(mo) |

hamtakuwa(mo) |

| wao |

-ko |

watakuwa(ko) |

hawatakuwa(ko) |

*NOTE: As you probably noticed, I had all the -po/-ko/-mo's in parenthesis for Past and Future tense. If you are mentioning a location in your statement, you can leave out the -po/-ko/-mo. It is only ESSENTIAL when you are not specifying a location in your statement (for obvious reasons).

Lastly, I will provide you with some example sentences:

| Pronoun |

Tense |

Kiswahili |

English |

| Mimi |

Present (+) |

Nipo hapa. |

I am here. |

| Sisi |

Past (-) |

Hatukuwa(ko) nyumbani. |

We were not at home. |

| Yeye |

Present (+) |

Yumo nyumbani. |

He is at home. |

| Wao |

Future (+) |

Watakuwa(po) kazini. |

They will be at work. |

*NOTE: Some nouns will add "-ni" at the end when talking about location. I do not know of a rule other than the fact that it seems to happen to most nouns.